Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture has acquired the largest collection of Phillis Wheatley’s work to date!

Phillis Wheatley Peters was born in Senegal, kidnapped from her home when she was around 7 years old, and enslaved in Boston. There she was sold to a prominent family, the Wheatleys, who named her after the slave ship she arrived on, the New York Times reports. In her enslavers’ home, Wheatley maintained a dual identity, as both servant and savant. Learning to read and write while enslaved, the family helped her publish her works as a poet. Wheatley then grew to prominence as one of the most prolific poets of the 19th century.

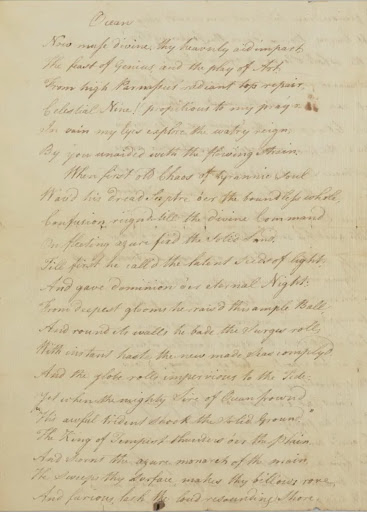

In September 1773, after traveling to London to promote her upcoming book, making history as the first published Black author in the United States, Wheatley returned to Boston again by ship, this time as a world renowned poet. It was on this voyage that she penned “Ocean,” a piece dedicated to the wonder of the moment and her simultaneous desire for freedom. While Wheatley’s first book catapulted her to fame, manumitted shortly after its release in December 1773, Wheatley failed to achieve similar success with her follow-up works. She married John Peters, a free Black grocer, in 1778. And while it is believed she had 3 children, none of them survived infancy and Wheatley eventually passed away in 1784.

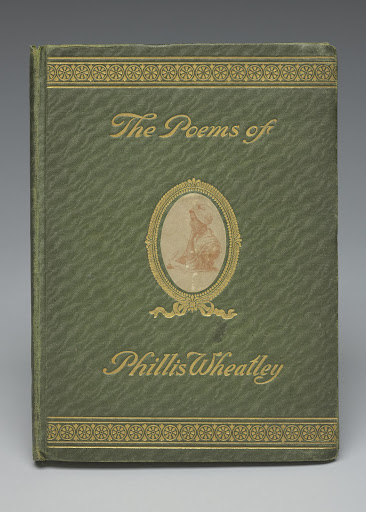

A copy of one of Wheatley’s poetry works from the Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

While Wheatley’s work brought with it controversy in the centuries after her passing, her impact on the abolitionist movement is undeniable, Wheatley serving as a figurehead for the antislavery movement. As for her work, “Ocean” went unpublished and was lost for more than 200 years, the manuscript resurfacing in 1998 at an auction. Now the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) has acquired the work, in what they’re calling “the largest collection of Phillis Wheatley material in public hands” to date.

“You’re seeing her handwriting, and seeing her write in this language she had fairly recently learned, and had become a champion of. And here she is in this moment where she has traversed the ocean, which she had initially done in a horrible way, but she was doing now as [a] celebrated poet. I’ve always thought of that moment and what it might have been like for her,” said museum director Kevin Young of the recently acquired manuscript.

A page of the unpublished 1773 poem “Ocean,” in Wheatley’s handwriting from the Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The collection includes 30 items featuring newspapers and books from Wheatley’s lifetime that include references to her and document her life after publishing. Young called the manuscript “stunning” as one of the only surviving Wheatley poems written by her. He also makes reference to an issue of The Boston Evening Post that announces Wheatley’s return for London alongside an ad for the return of a runaway slave named Nancy who would’ve been about Wheatley’s age, all published just before the Boston Tea Party incident.

“This is all the contradictions of this American moment,” explained Young.

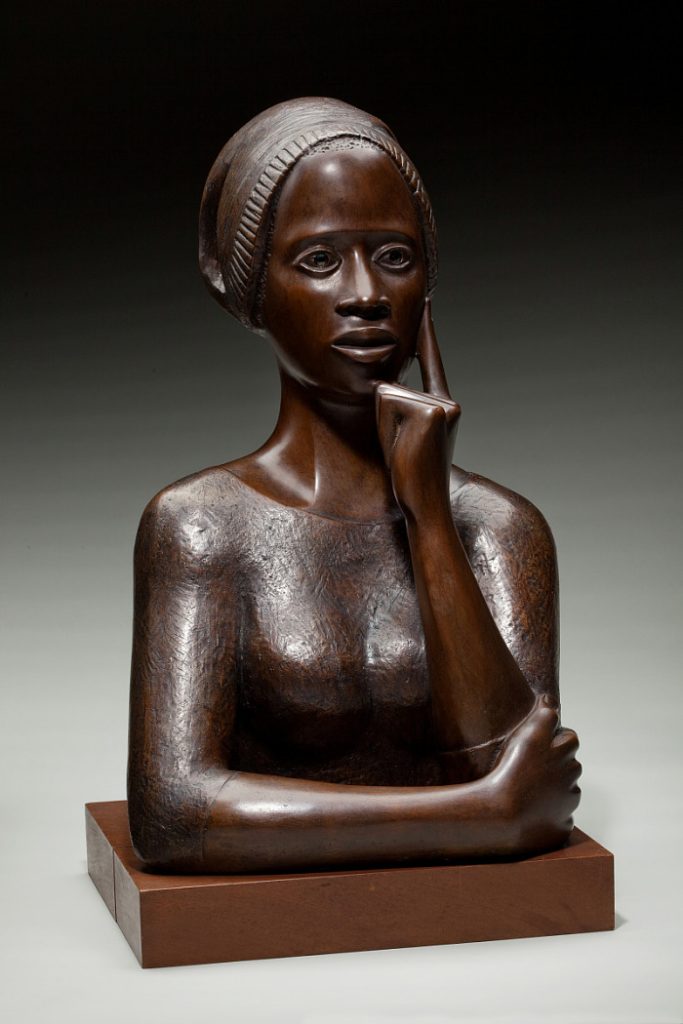

The NMAAHC already holds several Wheatley artifacts including a copy of her 1773 book “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral,” and a statue of Wheatley that features an inscription of the Declaration of Independence. The newest acquisition was brokered through dealer James Cummins, and includes items that speak to her prominence and early scholarly efforts documenting work and impact.

The Black Arts Movement of the 1960s brought criticism for Wheatley but in recent years, her work has been revisited and praised by poets like Nikki Giovanni and Amanda Gorman. Wheatley is also featured in the NMAAHC’s “Afrofuturism” exhibit, showing the writer’s work as a part of a larger continuum of African American history makers who were actively crafting the future and reimagining new possibilities through their life and work.

Young said the newest collection will help people to connect with Wheatley and her work in a way that we’ve never been able to before Not only will it give more context to her life and her work as it existed at that time, but also to the art of poetry then, which was less about personal experiences and more about the public affairs of the time.

Photo by Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture