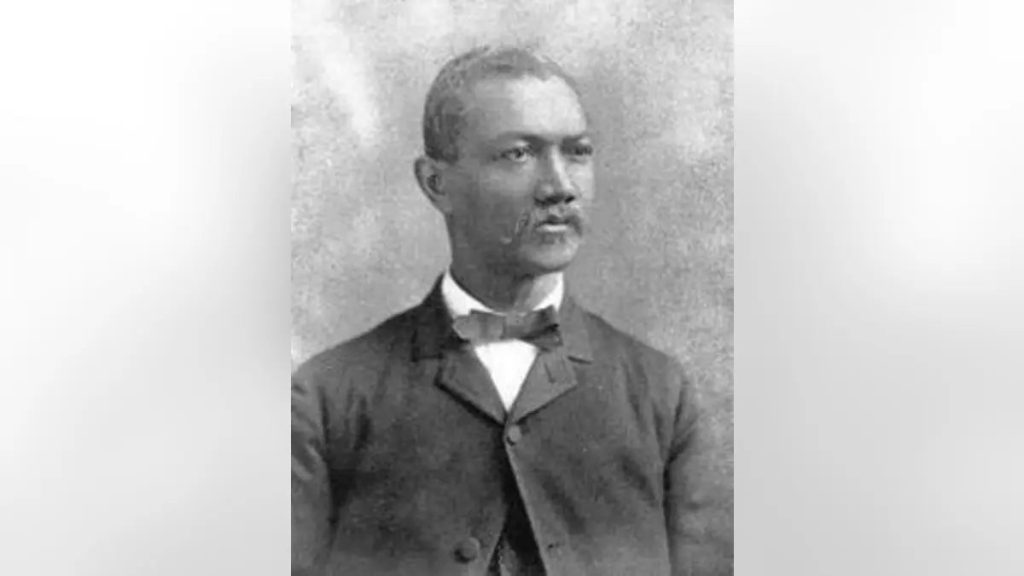

Happy birthday, Dr. Augusta!

The story of Dr. Alexander Thomas Augusta is quite remarkable. During a time where we have only been taught that Black people across the U.S. were enslaved, Augusta was building worlds and moving mountains through sheer intellect, resistance and skill. We wonder what knowing about stories like Augusta’s may do for our future children, for their own identity. We wonder how it will affirm their belief in what’s possible. That’s why we’re committed to telling his story and making sure it’s never forgotten. Here’s why you should know Dr. Augusta, the U.S. Army’s first Black doctor.

According to the National Park Service (NPS), Alexander Thomas Augusta was born to free parents in Norfolk, Virginia on March 9, 1825. He found his calling early, wanting to be a doctor since he was a young child and spending his youth educating himself despite it being against the law for Blacks to read and write. As an adult, he moved to Baltimore before settling in Philadelphia where he attempted to gain entry into medical school at the University of Pennsylvania. He was denied but found a professor who agreed to secretly tutor him, working as a barber on the side to support himself.

He eventually moved back to Baltimore, marrying Mary O. Burgoin before the two migrated to California. Given the 1852 census lists putting Augusta as a barber in El Dorado County, California, it is likely the couple headed west as part of the California Gold Rush. Eventually, the couple left and made a home in Toronto, Canada, a city welcoming to African-Americans that offered more opportunity. In Toronto, they planted roots, Augusta opening an apothecary and his wife Mary becoming one of few women of color entrepreneurs, opening the “New Fancy Dry Goods and Dress Making Establishment.”

Together, they built a life for themselves, settling in Toronto’s first working-class suburb and using their newfound stability to offer opportunities for other people of color. Augusta continued working on his degree in Canada, graduating with a Bachelor of Medicine degree from Trinity College in 1856, the president calling Augusta one of the most “brilliant students.” Augusta then launched his own practice, accepting all patients regardless of income or race and was later appointed as head of the Toronto City Hospital.

Augusta became president of the Association for the Education of Colored People of Canada and drafted a resolution for the Canadian Parliament formerly opposing an anti-Black candidate. A serious advocate for equality, Augusta even made the difficult decision to leave his all-Black church in protest of segregation in Toronto. When the U.S. entered the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation was signed on January 1, 1863, Augusta knew that his efforts would best be served back in his home country. On January 7th, he wrote to President Lincoln and Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War, requesting “an appointment as surgeon to some of the coloured regiments, or as a physician to some of the depots of freedman.”

He soon received an appointment confirmation, and Dr. Augusta and his wife set out for the United States with the hopes of supporting Black soldiers and the Union army. When he arrived, there was pushback; Augusta was thrust back into the racist soil that is America. Just two days before his U.S. Surgeon General exam to prepare for duty, he received a letter claiming his appointment was “recalled” because he was Black. The letter also noted that due to his Canadian status and Great Britain’s proclamation of neutrality, his appointment would violate those terms.

But Augusta refused to accept defeat and wrote again to President Lincoln, noting his desire to be of use and the high rate of Black servicemen in comparison to their white peers as evidence of his need. On April 1st, the Medical Board reversed the decision and on April 14, 1863, Augusta was commissioned as a surgeon with the rank of Major in the Union Army’s 7th U.S. Colored Infantry at the age of 38, the first of eight Black doctors to be commissioned to the Union Army.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BBYNJksBBKZ/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y=

Augusta’s first station was at Camp Stanton in Maryland but upon his arrival as the highest ranked doctor among a team of white surgeons, he was met with immediate discrimination. Some of the doctors even wrote to Congress to demand that “this unexpected and unusual, and most unpleasant relationship in which we have been placed may in some way be terminated.” To them, having to work with a Black doctor was “humiliating.” Congress obliged and the War Department relocated Stanton to Camp Barker in Washington, D.C. The move worked in his favor and Stanton made history as the first African-American to serve as head of a U.S. hospital, a position he held until the spring of 1864. From there, he went to Camp Belger in Baltimore where he was responsible for examining new Black soldiers, but before he left D.C., he would once again push back against racism.

In February 1864, while Augusta was attempting to board a horse-drawn street car in the rain, he was denied entry by the conductor who demanded he ride on the outside platform due to his race. Dressed in full military uniform, Augusta refused, citing the storm and his need to be protected from the rain, and was subsequently pushed out into the street before the car departed. Augusta wrote about his experience in detail to a D.C. judge advocate who forwarded the issue to Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, a sponsor for a bill prohibiting streetcar segregation. Sumner, a known abolitionist, recounted Augusta’s story on the Senate floor, arguing that it was a stain on the country and worse than being defeated in battle. A year later, in March 1865, legislation was passed making streetcar discrimination illegal, another win for Augusta.

Despite the progress he was making, Augusta understood that it was the bare minimum, and there were more wars to be fought. When Augusta first was commissioned as an officer, he was given a salary of $169 per month for his role as a surgeon with the rank of major. However, at the time, all enlisted soldiers of color were only paid $7 a month in comparison to white privates who received $13 monthly. In 1864, the chickens came home to roost when the Army paymaster refused to pay Augusta more than $7 a month. But never one to back down, Augusta took his complaints to Senator Henry Wilson, chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs. The issue was rectified and in June 1864, Congress established legislation allowing equal pay for all U.S. soldiers, regardless of color. For his efforts, Augusta earned the respect of his military peers and was given an honorary rank of lieutenant colonel, making him the highest-ranking Black officer in the military at the time.

That new prestige also earned Augusta an invitation to the White House from President and First Lady Lincoln on February 23, 1865. He gladly accepted and despite he and his assistant, Dr. Anderson Abbott, being met with trepidation by some guests, their presence made the Washington Chronicle, sparking more accurate media reporting of African-Americans who ranked in service. Some months later when Lincoln was shot by an assassin, it was Augusta’s assistant who would be called as an attending physician at his deathbed.

After the war, Augusta went on to serve with the Freedmen’s Bureau medical division and as an assistant surgeon at the Lincoln Freedmen’s Hospital in Savannah, Georgia. He eventually moved back to D.C. and launched his own private practice in 1868, hired a year later by the newly created Medical College at Howard University, making history again, this time as the first Black medical professor in the U.S. Augusta continued to make strides despite the racial oppression persistent at the time, creating the National Medical Society after being denied membership to the Medical Association of the District of Columbia.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CLM3MvZBLIr/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y=

He passed away at the age of 65 in 1890, records showing his wife continued to live in Baltimore in the St. Francis convent even after his death. Even in death, he continued breaking barriers, becoming the first Black officer-rank soldier to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery, his final resting place being section one, a location previously reserved solely for the graves of white soldiers. Despite his short time on earth, Dr. Augusta made more progress than some do in 10 lifetimes and opened numerous doors that can never be closed. It was Augusta’s sacrifices and perseverance that paved the way for equality in the medical field and in the U.S. Army. We remember his contributions on this day and everyday. Because of him, we can.

Here’s why you should know Alexander Thomas Augusta, the U.S. Army’s first Black doctor/Photo Courtesy of the National Park Service