Photo: Pam Kragen

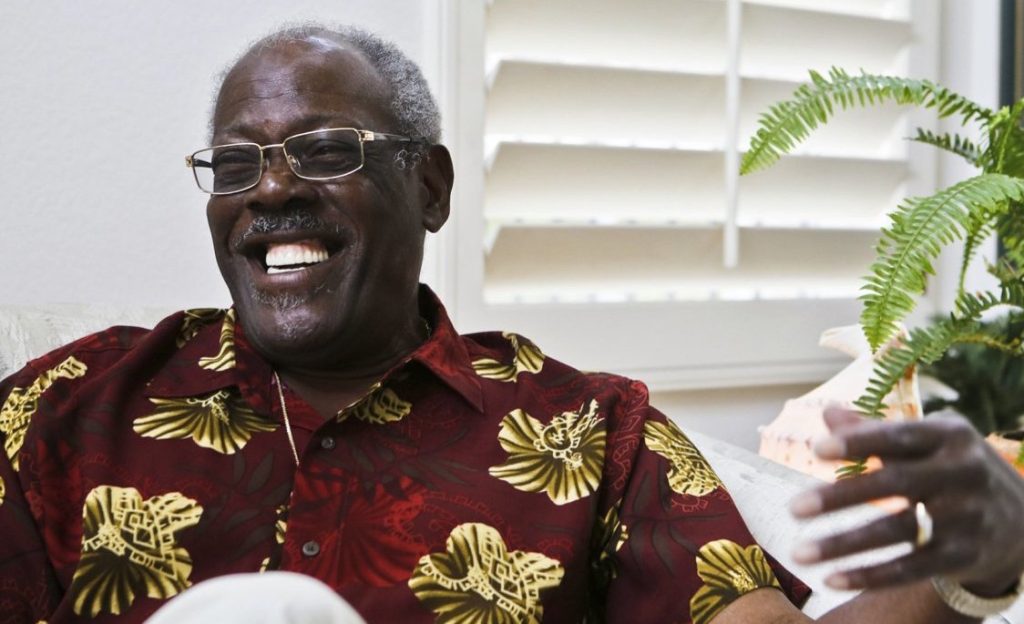

When the unmanned Apollo 6 rocket launched in the spring of 1968, it carried with it a camera that took images in space that had never previously been captured – thanks to the vision and work of Black NASA engineer, Shelby Jacobs.

A native of Santa Clarita Valley, California, Jacobs’ early experiences as a part of the one percent Black student population of his high school class soon prepared him to excel in the face of overt prejudice and low expectations. He became a standout athlete, student body president, and ultimately earned a scholarship to UCLA. While he intended to study mechanical engineering, his high school principal warned him that because of his race he may face some difficulties in the field.

“I didn’t translate his comments negatively,” Jacobs told the L.A. Times. “He was letting me know the playing field was not level, and I appreciated his honesty.”

He enrolled in UCLA in 1953 and immediately began to immerse himself in his studies. After three years on campus, he was then hired into a space program that built rockets used in Mercury, Atlas, Jupiter, and Thor programs. At that time, there were 5,000 engineers in this program and only eight of them were Black. While attempting to assimilate as best he could amongst his white counterparts, Jacobs endured never-ending racial comments, overt discrimination, and often had to challenge their misinformed assumptions about Black people. He was also paid significantly less than those who were performing the same work that he was.

Photo: NGV

Photo: NGV

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy announced the Apollo Space Program and Jacobs transferred to Rockwell in Downey, California. It was here that he worked for three years testing and perfecting the new camera system that ultimately accompanied the Apollo 6 rocket into space to capture some of the first documented images taken in space. While the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. casted a dark cloud over the year 1968, after the successful space launch Jacobs continued to thrive in the space program and garner various promotions. He ultimately retired in 1996.

Photo: Don Boomer

In 2009, Jacobs was named an “unsung hero” by NASA. He and his wife were also inspired in 2016 after the release of “Hidden Figures,” to advocate for equal compensation for persons of color and women engineers – as well as also encourage museums not to leave out the contributions of Black people to advancements in the aerospace industry.

The Columbia Memorial Space Center in Downey, California now features an exhibit entitled, “Achieving the Impossible: The Life and Dreams of Shelby Jacobs,” that will run through the spring. In honor of Black History Month, the museum will also have a daylong program on February 16.